The Oliver Mowat Expedition

The Oliver Mowat Expedition

Thousands of Bad Photos

September 30, 2023

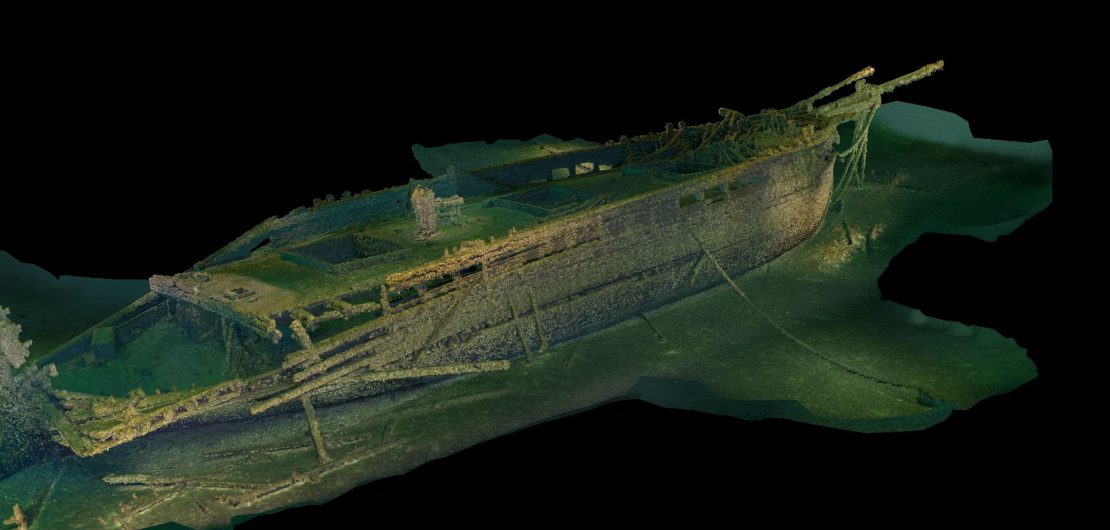

Cover Photo: 3D Photogrammetry Model of the KATIE ECCLES

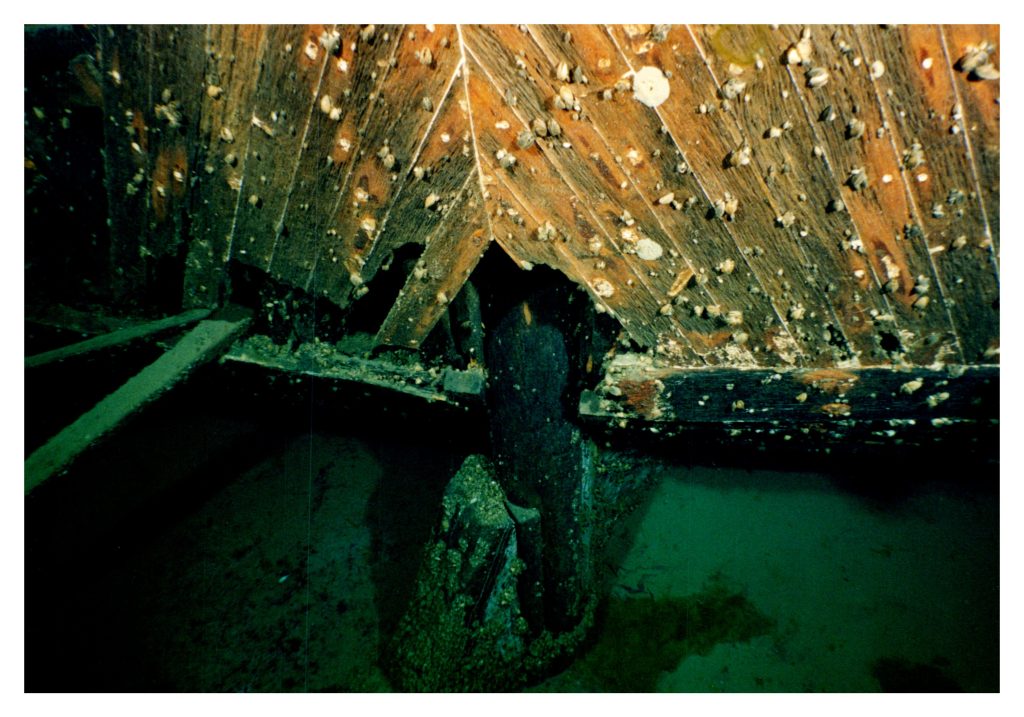

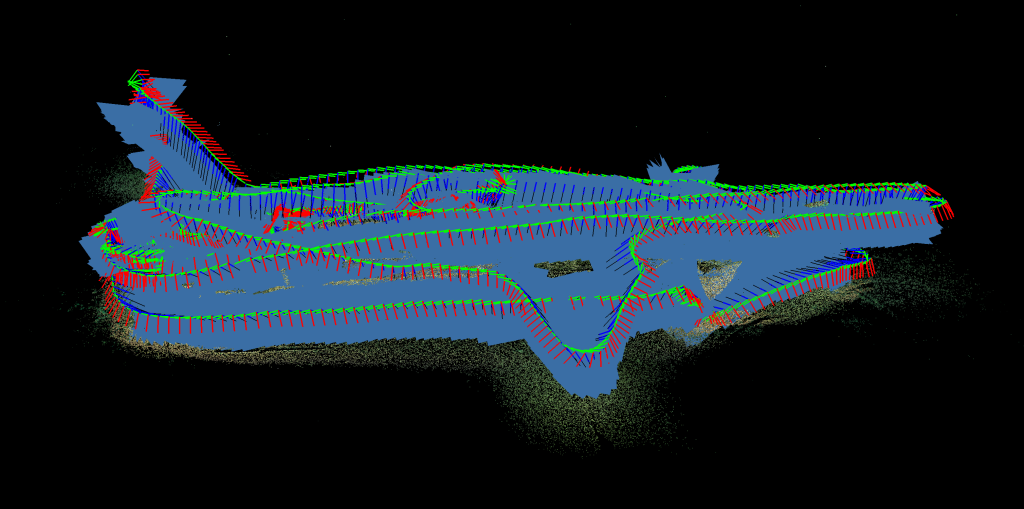

In exploring and documenting the OLIVER MOWAT, one of my goals is to create a 3D Photogrammetry Model. A detailed model will be a key element in the official archaeology report that will be sent to the Ministry and available to the public for research.

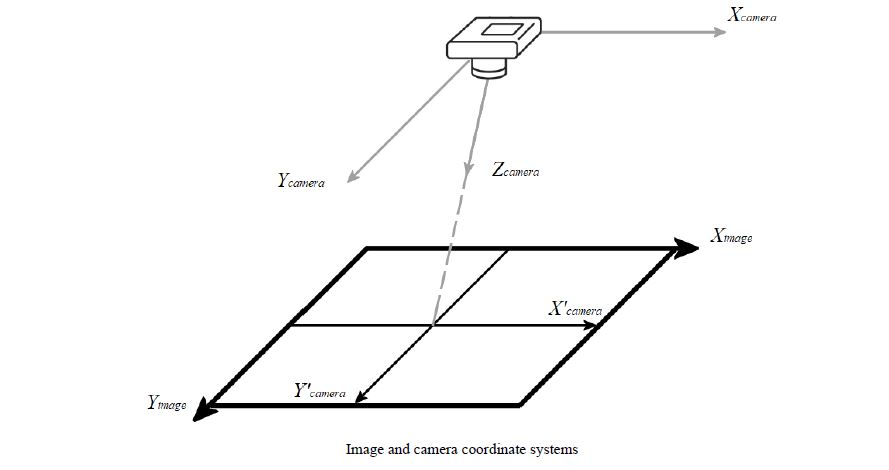

While I joke that photogrammetry is the art of taking thousands of really bad photos it is actually all about math.

The technique dates back as early as 1480 with Leonardo da Vinci’s research on perspective. The modern version started in 1867 and was called Die “Photomatomic photography” and was the start of three-dimensional measurements from two-dimensional data.

The first software was created in 1929: It was used for mapping and called “Stereoplan”. Developed by a German engineer it used satellite imagery and revolutionized photogrammetry, allowing for the creation of accurate maps and 3D models on a global scale.

The modern software available today is much more powerful and sophisticated and is capable of rendering very detailed models which can be rotated and viewed from any angle.

To achieve this quality, you need to capture thousands upon thousands of overlapping high resolution photos that cover every inch of the wreck.

While the team has already captured hundreds of artistic photos during the expedition, none of these are usable. Photogrammetry requires photos that are close and very squared up, plus are brightly lit to the point of almost being washed out and overlap the next photo by fifty percent.

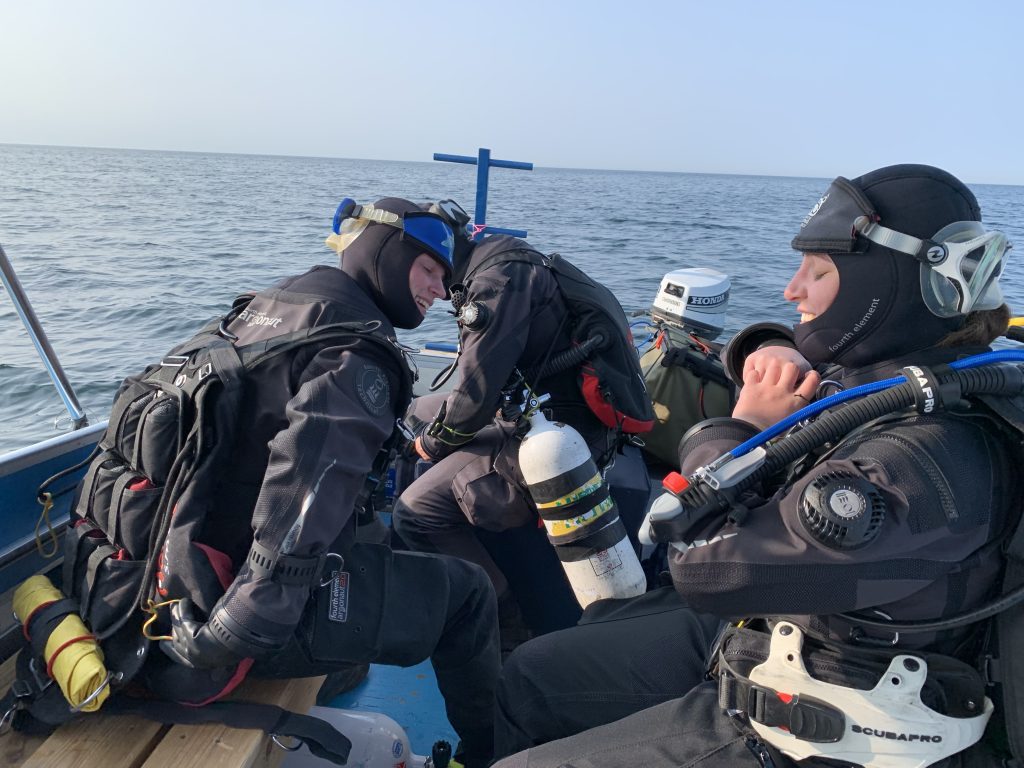

To capture this data requires a very carefully planned dive that will ensure every inch of the wreck was covered. The best results are achieved if all of the photos are captured on the same day so that the lighting is consistent. To do this the plan involved two teammates.

The first diver would use a camera mounted on a scooter with four large flood lights. The diver will circle the wreck three times working slowly from the bottom up to photograph the sides of the hull with the overlap required. Then make several passes across the deck to connect the sides of the hull to the top. While this sounds easy, remember that time is limited at these depths and every minute counts, so an exact path was laid out in advance. Plus, it is important to keep the camera at the same distance from the wreck at all times which is VERY challenging when circling elements like the bowsprit, masts and crow’s nest.

The second diver again had a very carefully planned route across the desk to capture the fine detail of the working components of a Great Lakes Schooner. Starting at the stern a spiral pattern is used to film the ship’s wheel from every angle. From there working towards the bow, this procedure was repeated for each of the other elements like the capstan, winch, donkey boiler, fife rail and windlass.

Late fall in Prince Edward County is a scene right out of a post card. The trees are ablaze of colour as you pass vineyards with farmers busy harvesting their crops. Arriving at our usual launch point, we were shocked as the habour looked more like a marsh. The water level was down a full two feet leaving the boat ramp high and dry with mud and rocks exposed.

With a perfect day of blue sky and no wind, we were determined to get out to the wreck somehow, so we attempted to launch, but had to abort when the sterndrive started to sink into the mud. Not willing to accept defeat we came up with a new plan and headed off to the marina at the small town of Waupoos. Launching from this location would add an additional ten kilometers to the wreck, but with the water flat and calm the trip was achievable.

After successfully launching the boat and loading up the equipment, I enjoyed the feeling of sun on my face and wind in my hair as we skimmed across the waves. Passing False Duck Island, I could imagine what sailors were feeling a hundred years ago as they headed out onto the lake with just a map and compass to navigate to ports far away.

At the site as we geared up to start our dive, we were shocked to see a paddleboarder approaching our boat. What was he doing here twenty-five kilometers offshore in the middle of the lake?

Pulling up alongside us, he wanted to check if we had broken down and needed help since he had never seen small boats out this far. After assuring him that we were fine, we enquired about his story. He explained that over the last several years he has been slowly circumnavigating Lake Ontario. Each trip he would pick up from where he left off, exploring both the shoreline and islands along the way. He was heading out to Main Duck Island where he planned to camp for the night. As he departed, we wished him well and warned him about the snakes that he was sure to encounter on his adventure. WOW, you never know what you will experience as you explore the waters of Lake Ontario.

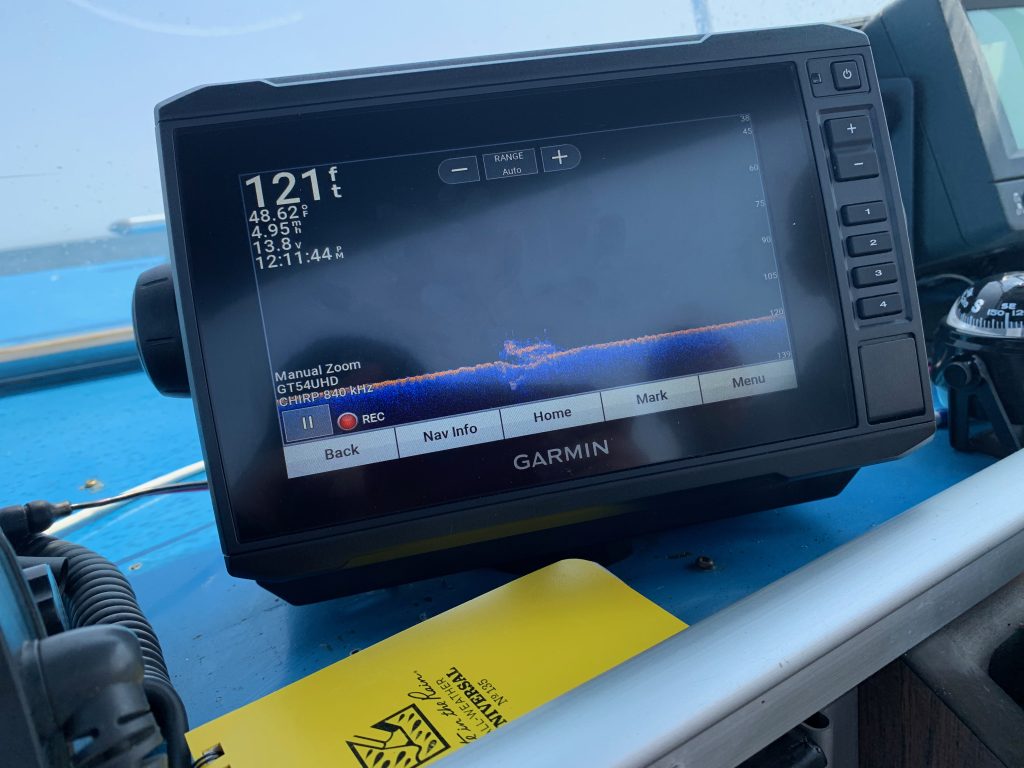

With the lake flat calm, we headed down the shotline to capture our photos. An hour later we were ecstatic as we climbed back onboard that the dive had gone perfectly to plan. With the sun sinking in the sky, we turned and started the long cruise back to shore. Anxious to see the results, we checked the cameras and were relieved to see that we had captured over eleven thousand photos.

The following day I started the long process of turning these photos into a 3D Model.

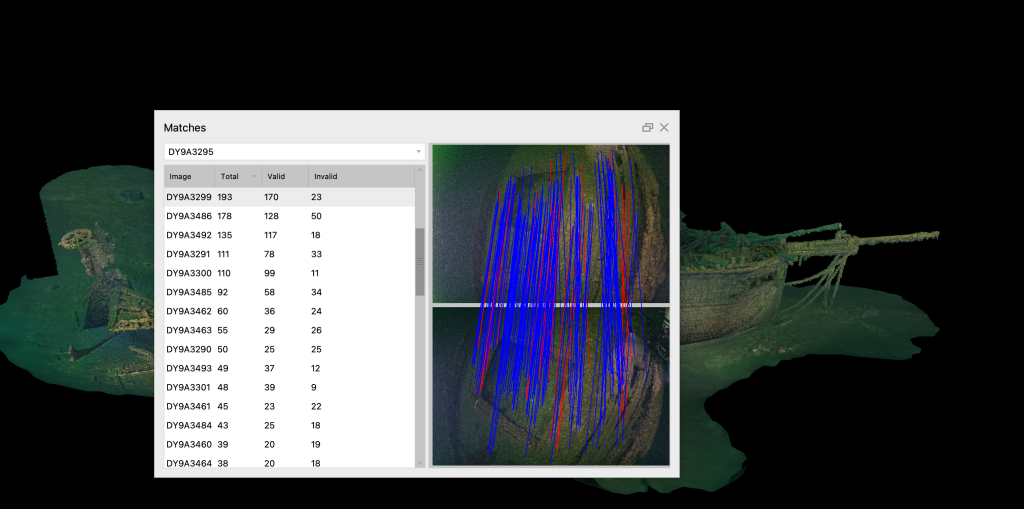

Even with a very powerful computer, the procedure will require several weeks of non-stop computing since we are creating a 4K resolution model. The software will create forty thousand data points on each photo and then compare each photo to the other eleven thousand in order to stitch them together.

After colour correcting the photos and importing them into the software, I had to patiently wait for two days for the first step to complete. When the alignment process finished, I was thrilled to see that I had achieved 97.7% accuracy. YES, we captured great photos!

Click HERE to view the interactive 3D model on https://3dshipwrecks.org/. Producing this type of model allows the public to explore the OLIVER MOWAT without having to dive into the cold depths of Lake Ontario.

It has been my honour to have been selected as a 2023 Royal Canadian Geographical Society Expedition Grantee and to lead my team members, Jill Heinerth and Charlotte Pilon-McCullough on this expedition.

Over the next several months, we will be sharing the story of our expedition at conferences, dive shows and in publications.

Sharing the story of the OLIVER MOWAT, The Era of Wind and Sail to the public will be our reward for all of the long hours underwater and hard work over the season!