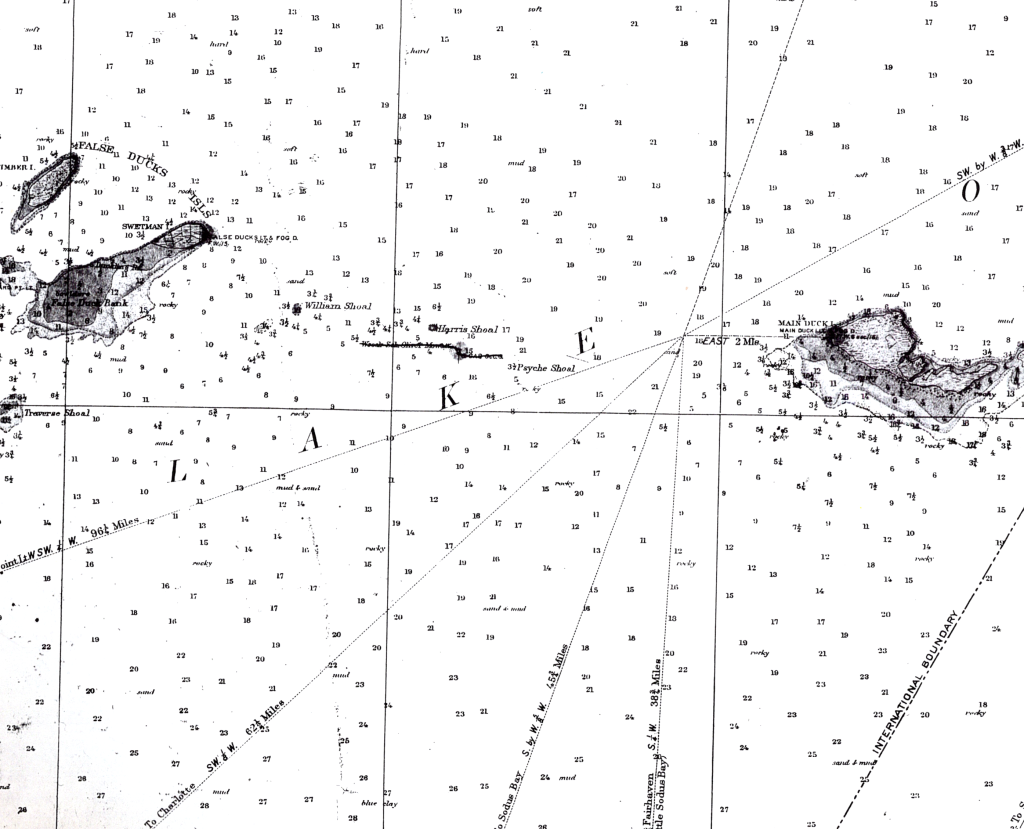

The Oliver Mowat Expedition

The Oliver Mowat Expedition

Planes, Trains and Automobiles

May 26, 2023

Cover Photo: Heading East to Picton, Ontario

As I start out on my expedition, I find myself in bumper-to-bumper traffic while towing a 22 foot boat. Despite the traffic my spirits are high with the anticipation of leading my team tomorrow in search of the OLIVER MOWAT. As traffic lightens and I finally get moving, I think about the differences in travel between the era of the OLIVER MOWAT and now.

In today’s day and age, we expect travel to be fast and efficient and we have a low threshold of tolerance for any delays.

In the 18th century there were no cars or freeways, so travelling on dirt roads was a long, dusty and tiring experience. A better alternative was to travel by train which was fast, comfortable and stylish. The downside was increased costs and a limited selection of routes and stops.

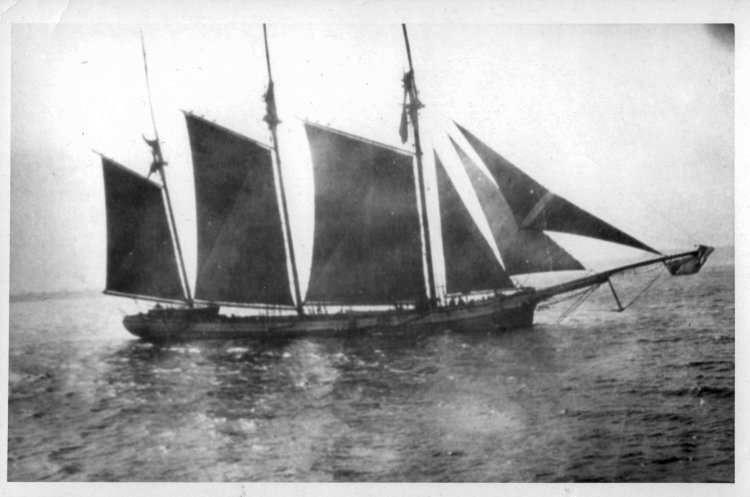

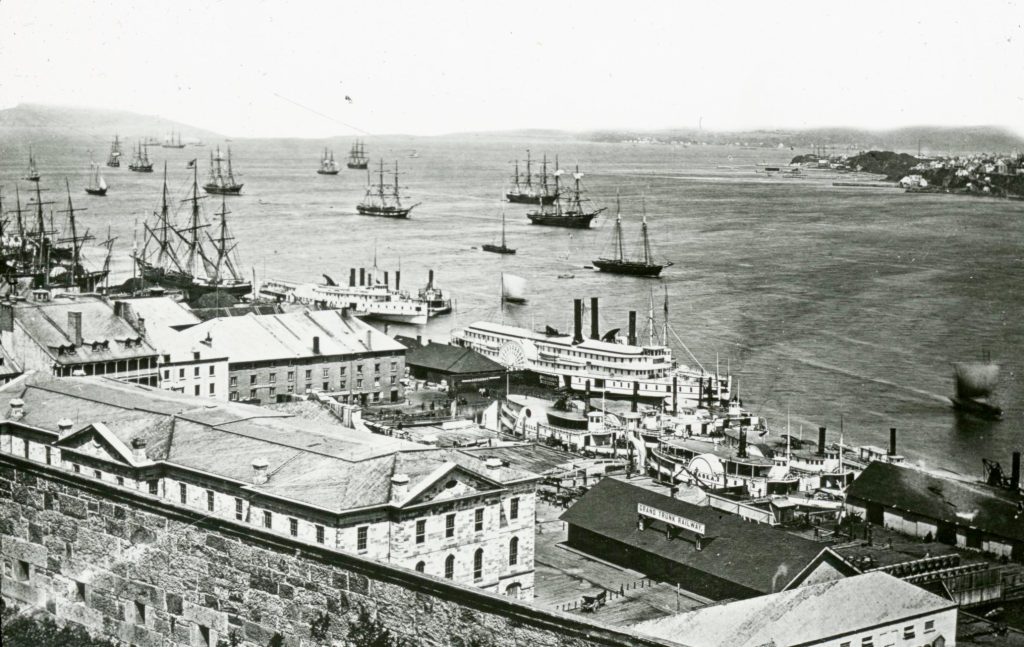

Schooners and the emerging steam ships offered an excellent compromise between the previous two modes of travel. Travel by ship offered lots of routes and ports of call at reasonable rates of passage. A range of accommodations were available from basic to luxurious; it was an unforgettable experience travelling on the open water.

Regardless of whether you choose carriage, train or boat, delays were expected and part of travelling in that era. While weather affected carriages and trains it had the greatest impact on sailing ships. No captain, either transporting passengers or cargo, would ever want to head out into foul weather.

Like travellers in the era of the OLIVER MOWAT, tomorrow as me and my team head out on our expedition our excitement about the journey and the joy of being on the lake with the wind in our hair is as great as the anticipation of reaching our destination.